The North Atlantic oscillation (NAO) is a climatic phenomenon in the North Atlantic Ocean of fluctuations in the difference of sea-level pressure between the Icelandic Low and the Azores high. Through east-west rocking motions of the Icelandic Low and the Azores high, it controls the strength and direction of westerly winds and storm tracks across the North Atlantic. It is related to and highly correlated with the Arctic oscillation.

The NAO was discovered in the 1920s by Sir Gilbert Walker. Similar to the El Niño phenomenon in the Pacific Ocean, the NAO is one of the most important drivers of climate fluctuations in the North Atlantic and surrounding continents.

Description

Westerly winds blowing across the Atlantic, bring moist air into Europe. In years when westerlies are strong, summers are cool, winters are mild and rain is frequent. If westerlies are suppressed, the temperature is more extreme in summer and winter leading to heatwaves, deep freezes and reduced rainfall.

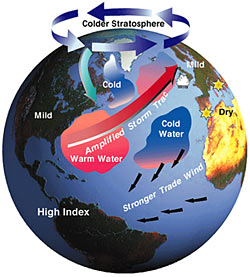

A permanent low-pressure system over Iceland (the Icelandic Low) and a permanent high-pressure system over the Azores (the Azores High) control the direction and strength of westerly winds into Europe. The relative strengths and positions of these systems vary from year to year and this variation is known as the NAO. A large difference in the pressure at the two stations (a high index year, denoted NAO+) leads to increased westerlies and, consequently, cool summers and mild and wet winters in Central Europe and its Atlantic façade. In contrast, if the index is low (NAO-), westerlies are suppressed, these areas suffer cold winters and storms track southerly toward the Mediterranean Sea. This brings increased storm activity and rainfall to southern Europe and North Africa.

Especially during the months of November to April, the NAO is responsible for much of the variability of weather in the North Atlantic region, affecting wind speed and wind direction changes, changes in temperature and moisture distribution and the intensity, number and track of storms.

Although having a less direct influence than for Western Europe, the NAO is also believed to have an impact on the weather over much of eastern North America. During the winter, when the index is high (NAO+), the Icelandic low draws a stronger southwesterly circulation over the eastern half of the North American continent which prevents Arctic air from plunging southward. In combination with the El Niño, this effect can produce significantly warmer winters over much of the United States and southern Canada.

No comments:

Post a Comment